Conversations around fast inference typically focus on one approach: blazing fast token generation with gargantuan models.

Both still play an important part in many circles. Models come in huge flavors, including Qwen (235B) and DeepSeek (631B). Some use cases, such as coding companions, demand high-quality responses that might only come from those larger models—and programmers are just as antsy as someone waiting on the phone for a customer service representative.

But many customer-facing applications are also quickly shifting to agentic workflows that demand fast completions to move on to the next step. A tradeoff has essentially emerged: how to deploy large agentic chains while balancing the need for high quality responses—which are typically associated with massive models like DeepSeek V3 or Qwen 235B.

The toolkit to address that problem, though, is growing to address the reality of AI inference: tokens-per-second is a dated concept, and end-to-end latency is what matters.

Optimized memory architecture that reduces the overall mileage—quite literally—for data transfer in a single AI inference addresses the biggest bottleneck in modern AI inference: the tax incurred by managing the state of a given AI inference. That makes an optimized hybrid memory architecture the best path forward to scaling up these applications to the next billion users.

Agentic flows become a multi-stage pipeline that has to manage the flow of context, which can be the initial prompt or the information from the prior inference. It also has to manage the state of the model—what model is currently available and ready for inference, as well as any parameters that govern that model’s behavior.

Optimized memory architectures offer significantly more flexibility. The models and their associated configurations—and along with any pre-set context—are stored in one type of memory until they’re needed. And when agentic networks need those models, it calls them to a higher-performance type of memory.

Hybridized memory approaches, like ones including different memory architectures—like an SRAM inference-based system coupled with smart DRAM usage—take advantage of some of the most important developments in AI:

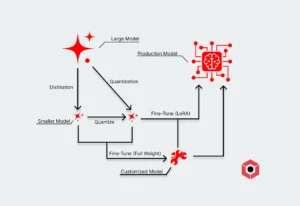

- Smaller models, which require significantly less memory, have become exceptionally capable. Models like Qwen (32B) and GPT-OSS (20B) are delivering a lot of bang for their buck. That smaller footprint is ideal for deployments using a hybridized DRAM-SRAM architecture.

- Larger models—like Llama 3.3–remain very performant, particularly in use cases where the quality requirements aren’t extreme, and fine-tuning satisfies both requirements. Agentic networks can call upon these larger-but-not-colossal models where needed, which still naturally fit to a scaled-up SRAM-based system.

- The focus on both massive memory pools and extreme token generation speed has opened a gaping hole in the middle: efficient and performant jumping to either extreme. A hybrid approach significantly reduces the penalty of the tradeoffs required that you would otherwise have in a classic GPU architecture.

This effectively creates a “middle lane” that avoids the need to massively scale up GPU deployment or pay for recompute costs. And middle lanes are great for enterprises.

Deploying SRAM in a scalable fashion alongside DRAM retains extreme latency requirements—another key requirement of agentic networks—while delivering an efficient scalable approach. SRAM can’t hold everything, but it can hold most of what you’re working on in a given step.

And there’s another new, sneakier requirement that’s come up: predictability. Using an SRAM approach can deliver consistent latency, meaning enterprises can reliably plan their app development on a stable framework.

The per-token compute for a given inference has become the “cheap” part of the inference process, while that movement to and from memory is a massive “tax” per token generation.

With per-token compute complexity coming down, the next step is to try to deduct that tax. Using SRAM does exactly that by shortening those trips to and from memory—literally—and spreading them out across a much larger number of cores.

Why The Lanes Matter Most Today

The KV cache is effectively what determines the next token—both in terms of quality and relevance. Each token generated updates the KV cache with new information. AI inference also requires a fully populated KV cache before generating the first token based on the prompt. The former is called decode, while the latter is called pre-fill.

Classic GPUs handle this process by moving data to and from the KV cache, stored on a type of memory called DRAM. But exclusively using DRAM—particularly using an HBM approach like those in classic GPU architecture—can also consume an enormous amount of power (on the scale of kilowatts per GPU).

DRAM in isolation scales up to massive models at the cost of using a classic, power-hungry HBM architecture. SRAM excels in executing smaller models and tasks but is more difficult to scale up the memory available. But using a hybrid approach gets the best of both worlds: SRAM is handling the “active” math in inference, and DRAM is storing everything else that isn’t needed at a given moment.

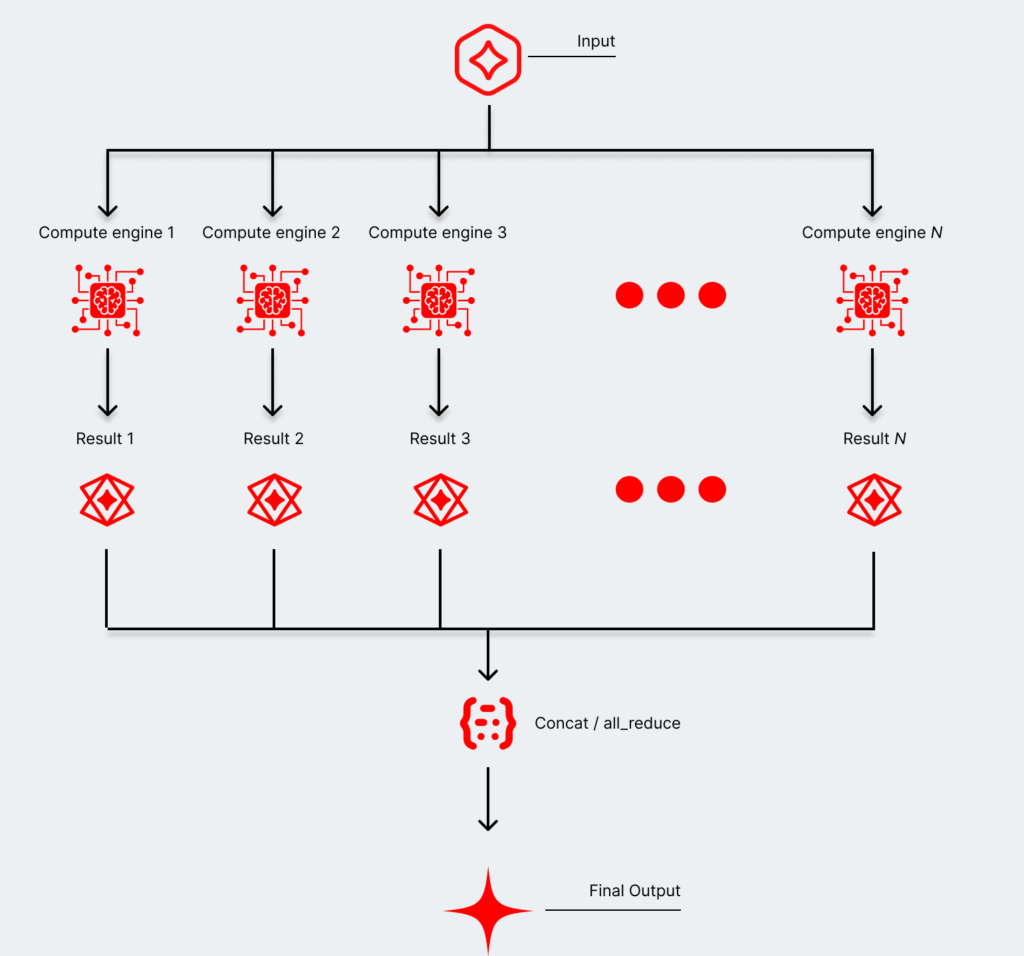

Agentic networks changed the center of gravity in inference as well, from a focus away from raw compute to memory and data orchestration. Applications that start scaling to the millions of users inevitably require more hardware. That requires managing the same high-performance requirements while adding more compute engines—they’re all part of the same system, but the pipes start to get longer and more easily clogged.

GPUs and some custom accelerators were designed with raw compute in mind. Optimizing the KV cache is instead a kind of emergent problem—we only figured it out after we started pushing out trillions of tokens, and enterprises started putting out serious products.

Using SRAM effectively shrinks the total distance traveled collectively. SRAM lives adjacent to — or on — the same substrate managing generating the new elements of the total KV cache. Instead of managing the whole thing, SRAM, which doesn’t scale to the size needed for colossal models, and connected compute cores are managing a small piece of it. In short, trips are shorter while moving less data.

Why SRAM (and DIMC) Is The Path Forward For The Rest Of Us

Multi-step AI-powered products don’t necessarily live and die on throughput. Instead, it’s built on a careful and highly optimized flow that depends on the prior agent finishing first, and more importantly reliably, rather than blazing through a pathway. Milliseconds add up, and failed responses cause the whole chain to go back to zero.

SRAM-oriented approaches are increasingly the way to tap that “somewhere in the middle”, satisfying a large number of use cases, providing predictability, and accounting for emerging developments like the prevalence of MoEs and the dearth of power readily available—if it isn’t already getting sucked up by companies with hundreds of thousands of GPUs.

The thought of building out a new kind of architecture after relying on GPUs for so long can seem daunting. However:

- Hybrid memory approaches exist in native form factors. You can just drop a card into an empty PCI slot.

- The results are immediate. Your power bill goes down while your performance goes up (and your product managers are significantly happier).

- Smaller, sub-100B models are only getting more powerful, further justifying focusing on these “other levers” than throughput and colossal models.

Most importantly, enterprises are increasingly focusing on results, not performance. Some use cases might need the most powerful GPU on the planet to solve an incredibly complex software engineering problem.

But talking to a voice agent either answers your question or gets you to the right place probably doesn’t need cutting edge GPUs. It has to be a snappy experience that scales up massively to millions of users—which is a different optimization problem altogether. Cost becomes critical, latency becomes the bottleneck, and predictability matters the most.